GPUs Part 1 - Understanding GPU internals

Written by Romit Jain

LLMs are pretty big and can use a lot of computing power. This makes them slow in terms of latency and makes them tougher (than ML models) to deploy. Hence, there is some alpha in learning how to run them as fast as possible, because that is what the real bottleneck currently is. If you can reduce latency or increase throughput, that opens up a lot of doors for LLM applications.

To learn how to run these big models as fast as possible, understanding the hardware (both CPU and GPU) on which they run is crucial.

This blog and others in the series (part 2) will help you learn about the basic layout of GPU hardware, a mental model of how the GPU programming model works, and how to progress from there to become a kernel master. (If you are asking, what’s a kernel, read till the end of the series)

PS, there is just a deep satisfaction in knowing how things work on the hardware. It gives you a deeper understanding of the models and an immense appreciation of all the abstractions.

Hardware

What is so special about GPUs that makes them extremely efficient for certain applications, especially LLMs? Understanding the hardware of GPUs is essential to answer this question. In one line, “GPUs are optimized for throughput whereas CPUs are optimized for latency”. In more lines -

Why are GPUs faster for LLMs?

The fastest way to run LLMs currently is to run them on GPUs. But why are GPUs faster than CPUs for LLMs? One valid answer is that GPU can process data parallelly because it operates in the SIMD fashion. CPUs are mostly designed to work with sequential tasks. But even then, what makes GPU process data parallelly? Majorly 2 things:

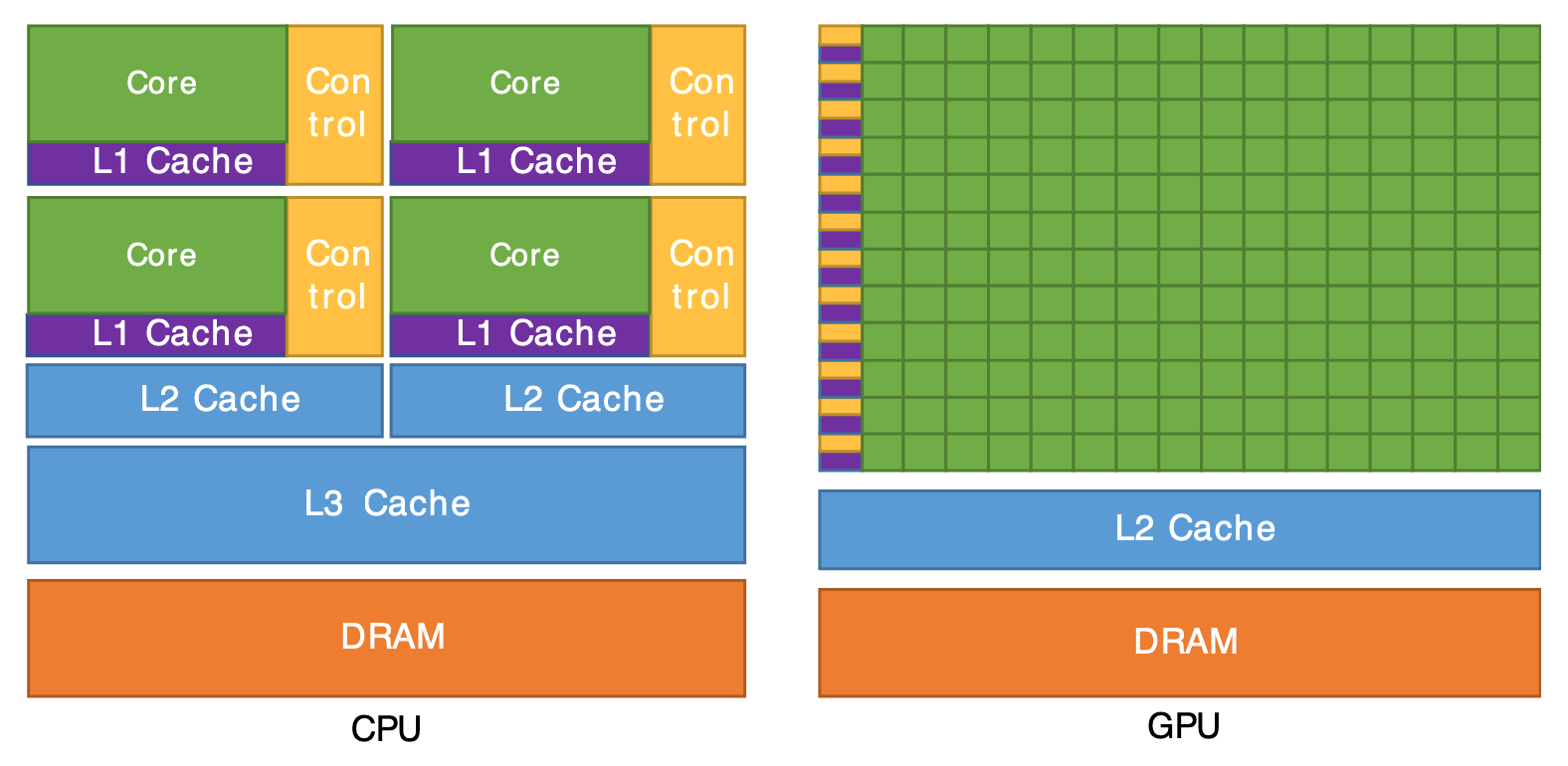

- CPUs have a lot of space on their chip dedicated to cache and registers. GPUs make a design choice that reduces the size of the cache and increases the number of cores. This way they can fit more cores in the same chip area. Cores are essentially the processing units that process data.

- CPUs have a lot of functionalities in their cores. These functionalities help them operate in a variety of different tasks and hence CPUs are very robust. GPUs reduce these special functionalities which helps it to reduce the size of the cores. If the cores are smaller, GPUs can fit more cores in the same area.

Figure 1: The figure above illustrates the differences in cache and control logic sizes between GPUs and CPUs. The GPU features significantly reduced cache and control logic sizes, as well as smaller core sizes. These tradeoffs allow for a higher number of cores in the GPU. Source

The more cores a GPU has, the greater the potential for parallel execution, leading to improved performance. However, it’s not solely about the number of cores. Other factors contribute to the overall efficiency and performance of GPUs.

GPU hardware layout

Let’s now understand how these cores are organized and arranged on the hardware.

CUDA Cores

Here is where the magic actually happens. These are the processing units of the GPU and come in different flavors, eg: Tensor Cores, Single precision cores, Double precision cores, etc. All of these cores handle different kinds of operations. The GPU decides where to send the operation based on the data type and instruction. The amount of operations these bad boys can do per second is what gives rise to FLOP numbers. Each of these different flavors has different performance numbers in terms of FLOPs because all of them do different kinds of operations.

For example, H100 has 16986 FP32 CUDA cores that can each do 2 floating point operations per cycle. The clock speed of the GPU is 1593 MHz. Theoretically, in total if all the cores are processing data at all times, it can achieve $ 1.593 * 10^9 * 2 * 16.986 * 10^3 = 54.1 * 10^{12} FLOPS$ or 54 teraFLOPs

This is close but not the same as what is shown on the official specs of H100. (I am not able to figure out the reason for the difference. If you know, please drop me an email!)

Streaming Multiprocessors (SMs)

All the cores in a GPU are organized into groups. Each of these groups is called a streaming multiprocessor (SM). Every SM has some memory associated with it. This memory can be shared amongst all the cores inside an SM but not by any other core outside this SM. This memory is called shared memory and is extremely fast in terms of data transfer speed or memory bandwidth. But this is also small in terms of capacity. So it’s essential to use this memory judiciously.

Why are GPUs divided like this? It’s to enable smaller groups of cores to share memory amongst themselves and work together. With every new generation of GPUs, typically SMs and cores per SMs go up in a GPU.

Let’s take some real numbers to understand the capacity. An H100 SXM GPU contains:

- 132 streaming multiprocessors (SM)

- Each SM has 128 FP32 CUDA cores (so a total of 16896 (132 * 128) CUDA cores)

- Each SM has 227 KB of shared memory

- And this memory has a bandwidth of 33 TB/s

SMs are also grouped into TPCs (Texture/Processor Cluster). For reference, the above hardware has 2 SMs per single TPC. But that can be safely skipped for now.

Memory

There are three kinds of memory on the GPU

- HBM/Global memory - This can be thought of as the equivalent of CPU memory. This is the slowest and largest memory available on the GPU.

- For reference, H100 SXM has 80GB of HBM with 3 TB/s of bandwidth (i.e. it can transfer 3 TB per second either to or from HBM)

- This is where the model is loaded when we do

model.to(device='cuda:0')

- L2 Cache - Faster than HBM but limited in size. This is shared among all the SMs.

- For reference, H100 SXM has 50 MB (lol, in comparison to HBM) of L2 cache with 12 TB/s of bandwidth.

- Shared memory - Fastest and smallest memory available on the GPU. Every SM has its shared memory and all the cores executing instructions in an SM have access to it.

Back to LLMs

Let me cite working examples to drive home a point - For LLMs, one should probably not worry about teraFLOPs. This answers the question that we asked at the end of the section Why are GPUs faster for LLMs? Take an example of the H100 SXM GPU that can do 67 teraFlops (FP32) of computation. The memory bandwidth of the HBM is 3 TB/s. That means the GPU can transfer about 3 TB of data to the compute layer per second. Considering FP32 (4 bytes), we can transfer about 750 billion numbers to the compute layer in one second. In contrast, the compute layer can perform 67 trillion operations per second. Just to break even with the computation speed, we would either:

- Need to transfer ~90x the data (67 trillion/750 billion) from the memory to the computer layer per second

- Or perform, ~90 operations on every data point each second

So, it’s tough to keep up with the computing power of the GPU. The bottleneck comes in transferring the data. There are three good resources on this topic to understand it better:

- NVIDIA docs

- An article by Horace He here.

- Another practical example is stated in the article: How is Llama.cpp possible?

Apart from the above, we also have warps in GPUs. Warps are a collection of 32 threads that are executed at once by the GPU. It’s slightly more complex to understand how warps work, so I will leave it out of the scope of this blog.

By now, you should be able to understand how GPU hardware is organized. There are a few other hardware concepts that I did not go through like warp scheduler, register files, etc. here, but that are not crucial to get started.

You are now all ready to start with the part 2 of this series.

Citations

For attribution, please cite this as

@article{romit2024gpus1,

title = {GPUs Part 1},

author = {Jain, Romit},

journal = {cmeraki.github.io},

year = {2024},

month = {May},

url = {https://cmeraki.github.io/gpu-part1.html}

}